Before Domino’s Sugar, there was Stuart’s Sugar in Tribeca

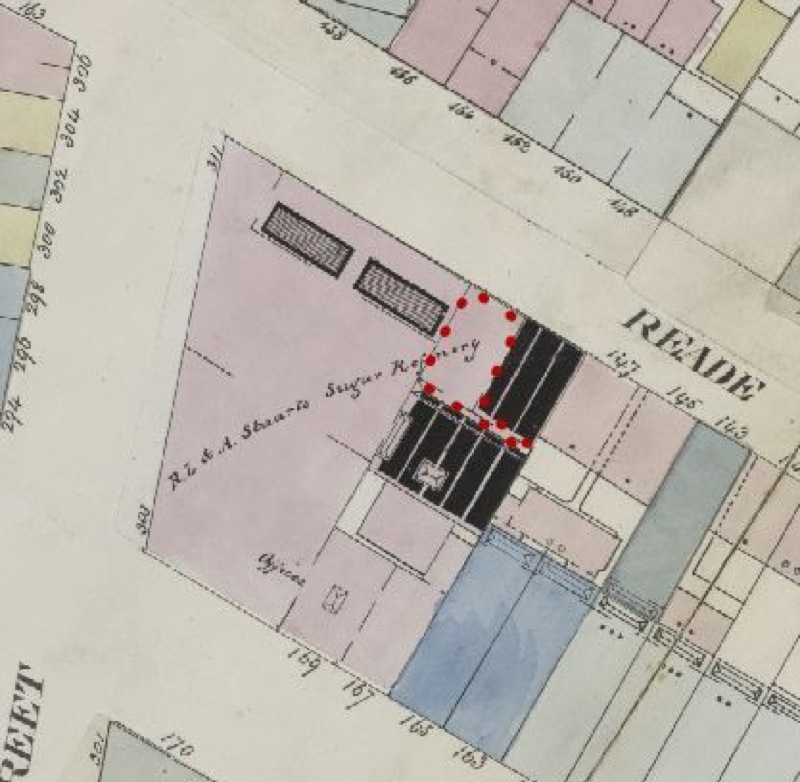

You are looking at before and after images made from the same spot, some 214 years apart. The top image is T. Pollock’s engraving of the magnificent Stuart Steam Sugar Company’s Refinery. The Stuart refinery was in two buildings that stretched from Reade to Chambers along Greenwich Street. The image underneath was made from the same location in 2014 and shows the new condo buildings that occupy the site. The small federal house on the far right corner of the top image was 169 Chambers Street. It was the home of one of the Stuart brothers.

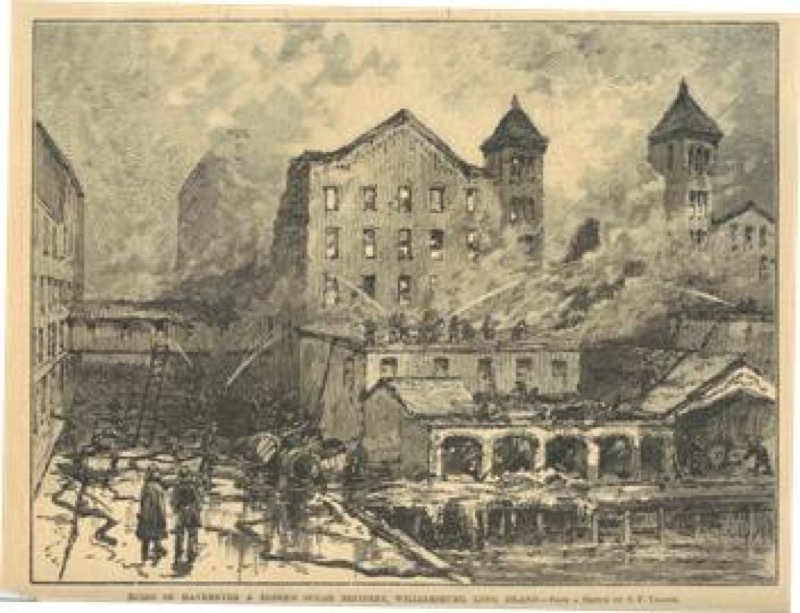

Stuart’s Steam Sugar Company was in the business of refining sugar and was not the only sugar refinery in Lower Manhattan. Havemayer’s Sugar Refinery opened on Vandam street about thirty years earlier (see image below from Brooklyn Historical Society). A third refinery on Laight Street is known to have survived a serious fire in 1852. There were surely others.

Havemayer’s Refinery on Vandam St.

But the Stuart’s were (according the Times) the first to succeed in using steam engines in the refining process. Sugar refineries became an important market for steam engines and a source of constant, incremental improvement of these engines throughout the industrial revolution in the United States. Didn’t someone say the Scot’s were responsible for the industrial revolution? Here is a one tiny bit of how that statement came to be made. The Stuart’s had annual sales of $3.5 million. According to an industry journal, they employed 321 men, used 45 million lbs of sugar a year, and 7-8,000 tons of coal a year. The raw sugar was hoisted to the top of the building, emptied into an immense copper, where the steam soon converted it to a fluid state. The product then drained through a purification cycle, finding its way to barrels at ground level.

The Stuart’s were old-school Presybterian Scots – meaning serious Calvinists. The Bible was considered the only relevant guide to decision-making and behavior for their family. Kinlock Stuart (portrait below) was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, arriving here in 1805 with $100 in cash and $7,000 in debt. He used his wife’s candy recipe to survive with a candy shop on Barclay Street. He made enough money such that when he died he had $100,000 to split between his widows and his two sons. The sons, Alexander and Robert, used their inheritance to enter the refining business. It is their refinery we see in the top image. The engraving was made sometime between 1845 and 1857. Alexander and Robert built adjoining houses at 167 and 169 Chambers Street. Robert married and moved up to 20th and Fifth. His vacated home at 169 Chambers became the offices of the sugar company. Alexander remained a bachelor and scion of local industry while living at 167 Chambers until he died. You can see their homes in the image above.

Kinlock Stuart

src=”http://tribecatrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Screen-Shot-2014-02-16-at-3.44.43-PMscaled.png” alt=”Screen Shot 2014-02-16 at 3.44.43 PMscaled” width=”636″ height=”800″ class=”alignnone size-full wp-image-2552″ />

In 1872, the two sons sold off the refinery equipment and rented out the building to other businesses. They retired and decided to live off rent income. They owned several other buildings in Tribeca by that point and were quite comfortable.

I do not know when the refinery was torn down and why it was not converted into loft dwellings like so many other buildings, and how the banal structure that replaced it came to be. Does anyone else know that part of the story? A Bromley map from the 1920’s show the refinery sitll there.

That stretch of Greenwich Street now hosts a series of post-modern, medium-rise buildings with brick skins that do not seriously offend, but they seem a sad replacement given the wonderful building that preceded it. Another enterprise founded by a Scot, McDonald’s, now anchors the NE corner at Chambers. While McDonald’s probably sells a respectable amount of sugar per year, their presence and the ordinary building they occupy seem a weak substitute for a real sense of place and history.