How is the Integrity of Historic Districts Maintained?

Historic Districts are cultural assets. Their integrity is a real problem. “Architectural integrity is defined as “those qualities in a building and its site that give it meaning and value” (Morton and Hume, cited in Murtagh, 2005).

It is very clear that from both preservation law and preservation theory “that the intent of regulation should be to maintain or restore the visual historical integrity of the district” (Murtagh, 2005). This can be done with regulations about architectural style, height, massing, color, materials, construction method, or adherence to a street wall. Most cities, but not New York, make these regulations transparent. Here is it done building-by-building, case-by-case, under ever-changing ideologies about architecture.

Despite the absolute clarity of intent in both national and local law and preservation theory, integrity is always under attack in New York City in particular.

There are four reasons for this creeping erosion of integrity:

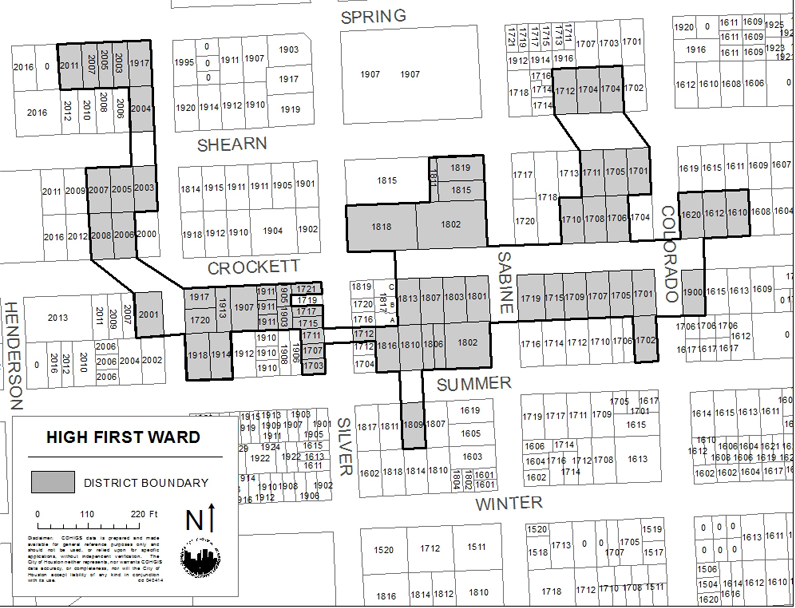

- Under-designation in the first place, meaning the original historic district is too small to defend its visual integrity against new construction right next to it. This usually happens in New York when the LPC draws a boundary through the middle of a block (or a building, as has happened) or when the regulatory body refuses to include historic buildings that have been subjected to some ugly modifications, even if restoration and repair is easy. The photo below shows a case in Texas where the same problem arose.

A subset of this problem is the making of excessive borders, as is the case of Tribeca and in the Houston case above. Excessive borders are a literal incentive for developers to take advantage of the values of the historic district by building as much as possible right on those borders. Economists call this behavior “free riding” and is a kind of market failure. It erodes the integrity of the districts as a cultural asset.

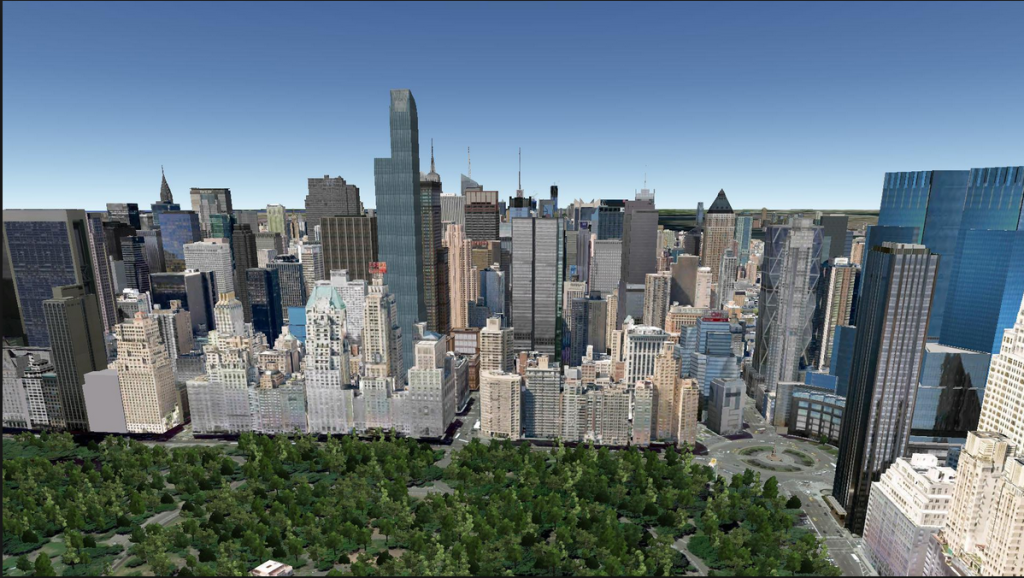

An example of free-riding (market failure) on a historic district at 56 Leonard. around landmarks and historic districts. This was proposed in the New York’s Landmarks Law back in 1966 but beaten back by REBNY (Wood, 2007).

2. The absence of a legal, more weakly regulated buffer zone around landmarks and historic districts. This buffer zone was proposed in the New York’s Landmarks Law back in 1966 but was beaten back by REBNY (Wood, 2007).

Not regulating a buffer zone around Central Park led to a “race for views” and another kind of free-riding on the resource of the park.

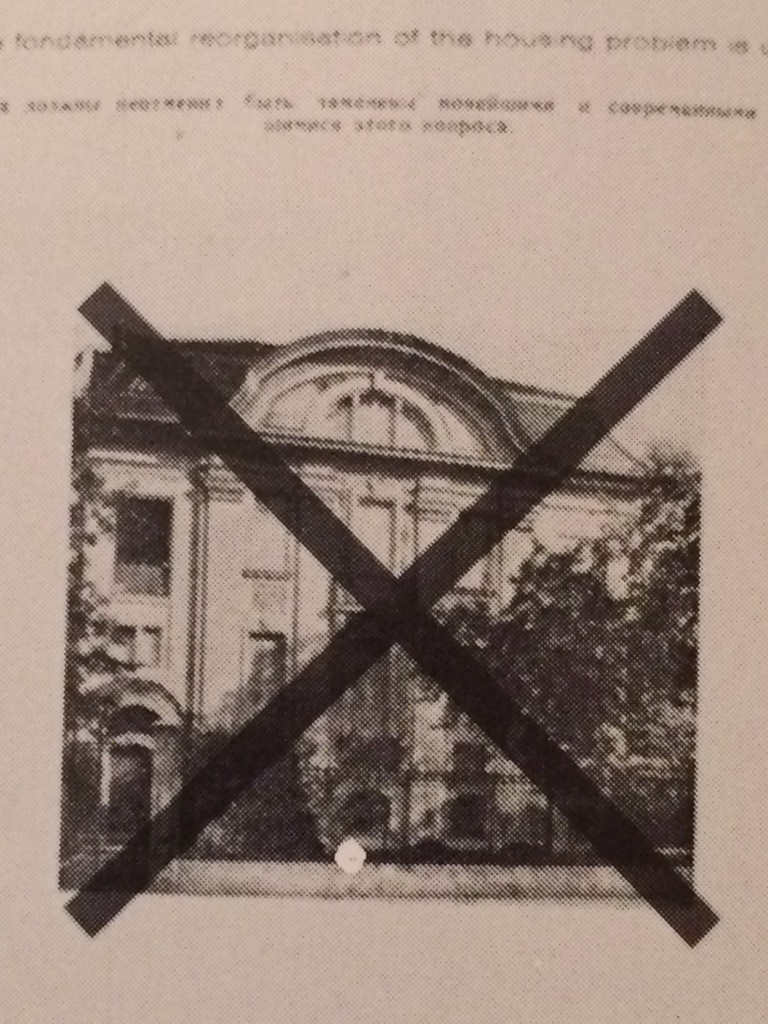

3. The misguided belief that architectural modernism as a style can be made to be “harmonious” or to “fit in” to a pre-modernist architectural styles, or even to treat the historical context as “a tryanny.” Those holding this fantasy forget that modernism as an architectural philosophy sought explicitly to stamp out historic styles, to dominate them, and to contrast as much as possible with those styles. Mies van der Rohe even published manifestoes with a big X over older architectural styles.

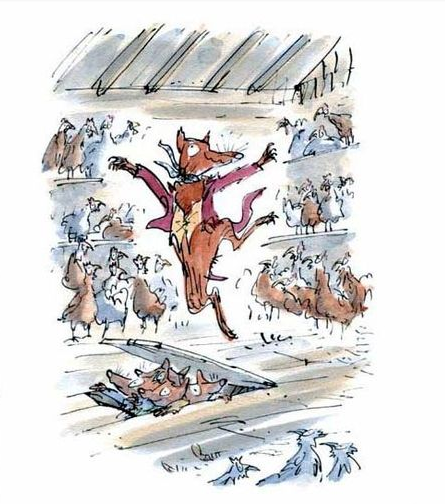

4. “Fox guarding the henhouse” situations when the regulatory body is essentially captured by anti-regulation groups or interests opposed to historical styles. They start doing things like caving in easily to pressures to build up and add extensions to historic building during real estate booms. This fox guarding the hen house situation can also happen when a modernist decides that the historical context is “a tyranny,” something that I personally witnessed at the LPC during the hearings over 100 Franklin last spring.

The fantastic Mr. Fox bringing his family in to raid the henhouse. Story by R. Dahl and illustration by Q. Blake

For more, check out the very nice book that the World Bank economics department came out with a couple of years back called “Economics of Uniqueness” or look to William Murtagh’s book, “Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America”