A letter from Christabel Gough Answers Some of Our Questions about the Environmental Impact Statement for ZQA/MIH

Last week we were scratching our heads at Gale Brewer’s hearing: where was the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for all these controversial zoning proposals? That document was going to explain the impact of the Mayor’s zoning ideas on all of our neighborhoods. Hmmm… Given that this is NYC and Big Real Estate runs the show, we could not help but wonder: is the process itself awry? Yesterday, Christabel Gough sent us some answers. We print her letter at length below. Spoiler alert: yes, the process is awry and the zoning creates serious negative impacts that “cannot be mitigated.” Ms. Gough also wins our understatement prize of the week for her concluding sentence of this essay.

Tribecans may wonder, who is Christabel Gough? The short of it is that she is one of New York City’s most articulate architectural critics and preservationists. She founded the Society for the Architecture of the City which long ago published Village Views, one of the more notable journals to come out of the preservation movement. Ms. Gough is a Landmarks Lion of the Historic Districts Council.

A Letter to the Tribeca Trust

Monitoring the ongoing public review of the Mayor’s “affordable” housing proposal, Zoning for Quality and Affordability, the Tribeca Trust Blog wonders:

“Some smart person asked, why are community boards voting when the Environmental Impact Study is not available? Good question. So far, I have not found an answer.”

There is an answer, though the answer itself raises a lot of questions. Going back to the beginning, in 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire and the cover of Time Magazine was an image of the water burning. This really got people’s attention, and concern about industrial pollution reached a pitch that required political action: the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the 1976 New York State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) and New York City’s 1977 Executive Order establishing City Environmental Review (CEQR).

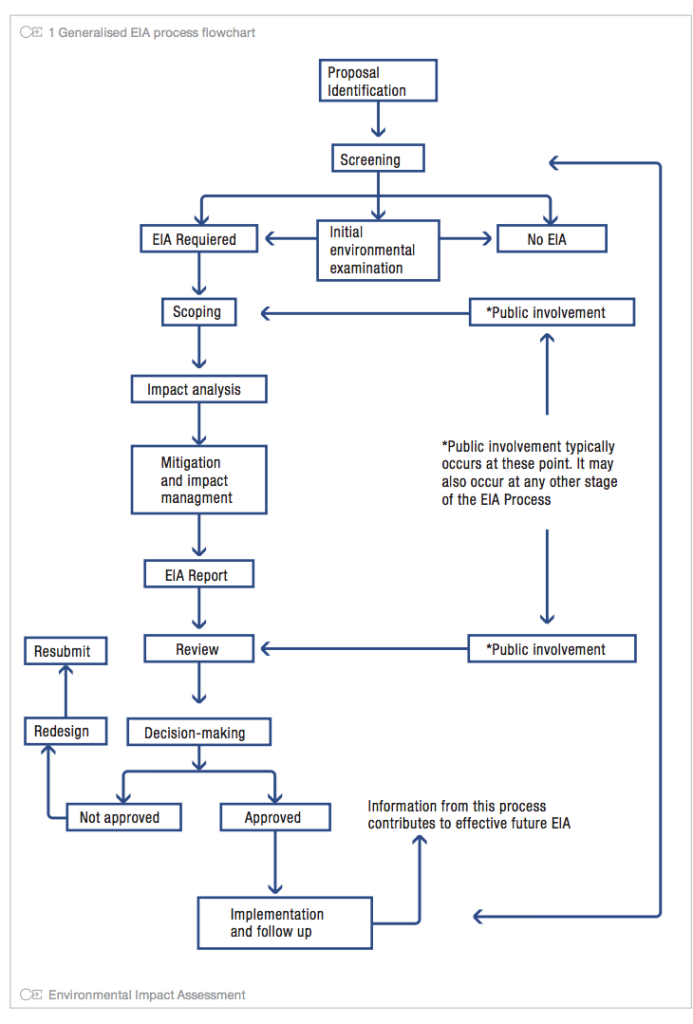

Naturally, no sooner were laws enacted than strategic attempts to weaken them commenced. One way was through administration, and our CEQR Technical Manual, first issued in 1993, has been revised repeatedly, usually under the radar, because the excruciating tedium of that heavy book of words discourages the press and the public, who would rather take it on trust that revisions (or indeed the manual itself) can have no sinister impact.

The ultimate fruit of CEQR, the Environmental Impact Statement, that well-known EIS, widely viewed as an important civic weapon, is supposed to inform decision makers about any environmental dangers involved in proposals they are reviewing. Theoretically, logically, this information would be available before the decision makers made their decision.

The Zoning for Quality and Affordability Text Amendment (ZQA), a much-hated proposal now making its way through the Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP) will soon reach the City Council for a decision. So where is the ZQA EIS? The answer seems to be contained in obscure sections of our revised CEQR Technical Manual (2014 version, Page 1-18, Section 245.1: Public Hearings and Page 1-23, Section 280: Regulatory Time Frames).

First, for ZQA, although environmental review was initiated, there is no requirement for it to finish in the otherwise usual manner, on schedule, with the production of a final EIS including responses to substantive criticisms made at an otherwise required public hearing on the draft EIS. No, according to the CEQR Technical Manual, proposals that go through the Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP) are different, and the Rules of the City of New York bear this out:

“Where a proposed action is simultaneously subject to ULURP, a public hearing conducted by the appropriate community or borough board and/or the City Planning Commission pursuant to ULURP shall satisfy the hearing requirement of this section. Where more than one hearing is conducted by the aforementioned bodies, whichever hearing last occurs shall be deemed the hearing for purposes of this chapter. (43 RCNY 6-10(c)(4))”

Thus neither the community boards nor the borough boards will have the benefit of any expert scrutiny and criticism of the draft EIS (a 1019 page document available on line [here] if you know when and where to search ) and further, the last hearing, the City Planning hearing, is “deemed the hearing,” so the angry population that turned out en masse for earlier ULURP hearings will not be part of the record in the environmental review process.

Proponents of ZQA may be glad of any obscurity, since one preliminary finding in the Draft EIS was that ZQA would cause significant negative impacts that could not be mitigated: including shadows and impacts on “historic resources.” [That would refer to] landmarks, old neighborhoods, and sunlight, things people want in their lives. (DEIS, page 30.)

Remember that this insight—significant adverse impacts that cannot be mitigated—emanated from the same source that drafted the ZQA, that determined that it required environmental review, that prepared the scope of work, prepared the draft environmental impact statement, and then apparently determined that ULURP precluded the need for calling an otherwise required public hearing within a 60 day time frame, substituting a later hearing of its own. Commissioner Carl Weisbrod, Director of the Department of City Planning and Chair of the City Planning Commission, is in charge of the whole process, because the CEQR manual assigns all zoning text amendments to the DCP as lead agency, and all zoning text amendments require ULURP, so the DCP is always in a position to avoid timely public and expert comment on a draft EIS written by DCP, by postponing a hearing meant to review a zoning text amendment also written by DCP.

It would have been nice if the public at large had been aware of this. But so far from alerting us to this interesting process, the DCP published and circulated to elected and appointed officials an announcement of the completion of the DEIS, which specifically stated that the public hearing on the DEIS would be announced. That was on September 18; the sixty day period during which the public hearing would normally have taken place expired, and people were still waiting, until just now, a December 16th hearing was obscurely published. ULURP took precedence, which seems to be acceptable practice under existing rules. Whether it is good government is another question. Professor Tom Angotti writes:

“The role of the DCP and CPC in environmental review is unique and fraught with serious contradictions and potential conflicts. When DCP is the applicant on land use and zoning matters, they are effectively the “lead agency” responsible both for disclosing potential negative environmental impacts and insuring that the environmental review is complete and the application can proceed through ULURP. This has created a clear conflict of interest. While DCP is an executive agency that acts in accordance with mayoral priorities such as encouraging new housing and commercial development, it is also the agency identified in the charter as the effective custodian of the land use review process. In practice, it is virtually impossible to separate these two functions when they are lodged within the same agency. Thus it should come as no surprise that all of the 101 executive proposals for zoning changes since 2002 were approved.”

But this time, even without benefit of a final EIS, the ZQA ULURP has generated one of the most massive public rejections of a zoning text amendment ever. Nevertheless, if environmental review functioned as perhaps ideally it should, with unambiguous, generally recognized public hearings, held before an application goes into ULURP, additional important concerns could come to light from private individuals with special knowledge.

In an instance when public comment worked, in 2003, Joy Chatel, owner of 227 Duffield Street, appeared at a hearing on the draft EIS for the Downtown Brooklyn Development Plan, to say that her house had sheltered fugitive slaves before the civil war, that it had been owned by known abolitionists, and so should not be taken by eminent domain and demolished to make way for an underground parking garage.

The Deputy Mayor for Economic Development, the lead agency, was obliged to publish a summary of her comments and a response in the final EIS, so the issue was aired, with the result that the Development Plan was held up at the City Council, which required supplemental environmental review to explore possible gross errors of fact in the EIS. Under these embarrassing circumstances, the EDC did not immediately pursue putting an elderly black widow out in the street through eminent domain to build a parking garage, and Joy Chatel lived out the rest of her life in 227 Duffield Street, all the while crusading to publicize the abolition history of downtown Brooklyn, which though considerable, was little recognized at the time. Walt Whitman had lived a block from Duffield Street when he wrote the famous lines beginning, “The fugitive slave came to my house,” in Leaves of Grass.

Also, a function of the ideal EIS is to examine alternatives. If there had been a public hearing on the ZQA DEIS before the start of ULURP, Charles Urstadt, who presided over the creation of Battery Park City, could have spoken, as he did to Juan Gonzales at the Daily News, about an unmentioned alternative, using the surplus revenues of Battery Park City originally earmarked for housing to fund billions in bonds that might make it possible to build low or moderate income housing without subsidies to private developers.

This is the kind of thing that can occur as a result of a public hearing on a draft EIS, so it is regrettable that the public process is what it is, especially in the case of a seriously debatable zoning proposal like ZQA. Draft environmental Impact statements have always been prepared by the sponsor of the proposal under review, and the role of the public hearing is to correct any bias that may result: without a public hearing on a DEIS, the document cannot be regarded as an impartial source of information, nor should summaries of it be accepted as necessarily comprehensive or factual. The community boards and the borough boards have been deprived of an important analytical tool, while flooded with biased summaries from the administration.

Note also that ZQA was presented for ULURP review in tandem with the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing Text Amendment, for which the DCP had issued a Negative Declaration, finding that it did not meet the criteria for environmental review. No one contested this, perhaps because the issuance of a negative declaration is an obscure administrative procedure which is published in the State Environmental Notice Bulletin but may still pass relatively unnoticed, until it is too late.

The growing complexity, obscurity and insularity of environmental review can make it less accessible to citizens who want to participate, to the detriment of its original mission.

Christabel Gough